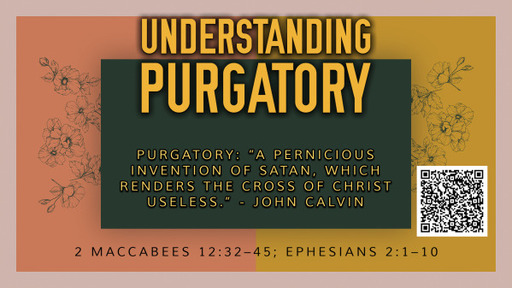

Understanding Purgatory

Notes

Transcript

Handout

This is the third weekend of the month, so we are answering questions in the Question Box.

The question this month is on Purgatory. There are two questions regarding it.

First, where does the idea come from?

Second, why do some denominations believe in it, and others do not?

Before I answer these two questions, we need to understand the concept of purgatory.

What does purgatory mean?

Purgatory is from the Latin word purgatorium. It signifies a place of cleansing and thus infers the process of cleansing. We derive the verb 'purge' from it.

The Catholics define purgatory as “a state of temporary punishment for those who, departing this life in the grace of God, are not entirely free from venial (forgiveable) sins or have not yet fully paid the satisfaction due to their transgressions, and the souls detained in it are helped by the suffrages of the faithful.” (Joseph Pohle and Arthur Preuss, Eschatology, or The Catholic Doctrine of the Last Things: A Dogmatic Treatise, Dogmatic Theology (St. Louis, MO: B. Herder, 1920), 77-79.)

Where does the idea of Purgatory come from?

It began with the 2nd-century Church practice of praying for the dead. There are records of such prayers in the catacombs in Rome, with prayers like “Lord, preserve Calendion for eternity in your holy name!” These kinds of prayers are far from the practices done by Catholic Christians on behalf of their dead brothers and sisters.

The first actual reference to praying for the dead is in the 3rd century in Tertullian's writing titled “Monogamy” in chapter 10. In this passage, he counsels a divorced widow to pray for her dead husband to rest in peace and for her to be at peace with him. To do so, she must pray for his soul, requesting refreshment and offering sacrifices on the anniversary of his death. Tertullian believed that if this were not done, then she would not be reconciled to her husband in the resurrection. (Tertullian. “On Monogamy.” Fathers of the Third Century: Tertullian, Part Fourth; Minucius Felix; Commodian; Origen, Parts First and Second. Edited by Alexander Roberts, James Donaldson, and A. Cleveland Coxe, Translated by S. Thelwall. Vol. 4. The Ante-Nicene Fathers. Buffalo, NY: Christian Literature Company, 1885.)

Origen, in the mid-3rd century, in his treatise “On Prayer”, has the saints in heaven praying for those still alive on earth. Nowhere does he mention Christians on earth praying for their brother and sisters who have gone before.

Arnobius, in the beginning of the 4th century, in his work “Against the Heathen”, has Christians praying for peace and pardon for the living and the dead, Christian and non-Christian. (Arnobius. “The Seven Books of Arnobius against the Heathen (Adversus Gentes).” Fathers of the Third Century: Gregory Thaumaturgus, Dionysius the Great, Julius Africanus, Anatolius and Minor Writers, Methodius, Arnobius. Edited by Alexander Roberts, James Donaldson, and A. Cleveland Coxe, Translated by Hamilton Bryce and Hugh Campbell. Vol. 6. The Ante-Nicene Fathers. Buffalo, NY: Christian Literature Company, 1886.)

It is in the 4th century, the concept that “praying for the dead helps them” is stated explicitly. Cyril of Jerusalem writes, “And I wish to persuade you by an illustration. For I know that many say, what is a soul profited, which departs from this world either with sins, or without sins, if it be commemorated in the prayer? For if a king were to banish certain who had given him offence, and then those who belong to them should weave a crown and offer it to him on behalf of those under punishment, would he not grant a remission of their penalties? In the same way we, when we offer to Him our supplications for those who have fallen asleep, though they be sinners, weave no crown, but offer up Christ sacrificed for our sins, propitiating our merciful God for them as well as for ourselves.(Cyril of Jerusalem, “Five,” in S. Cyril of Jerusalem, S. Gregory Nazianzen, ed. Philip Schaff and Henry Wace, trans. R. W. Church and Edwin Hamilton Gifford, vol. 7, A Select Library of the Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers of the Christian Church, Second Series (New York: Christian Literature Company, 1894), 154–155.)

Jumping ahead in our timeline, at the Council of Lyons in 1274, Purgatory is articulated as a doctrine.

The Council of Florence in 1439 defined it as both penal and purificatory in nature.

Lastly, in 1563, the Council of Trent recognized the validity of suffrages performed for the benefit of those in purgatory. (Robert Stewart, “Purgatory,” in Holman Illustrated Bible Dictionary, ed. Chad Brand et al. (Nashville, TN: Holman Bible Publishers, 2003), 1350.)

It is in these councils that 2 Mac. 12:32-45 is used as a proof text for this doctrine. Let's look at part of that passage.

And Judas gathering his army came unto the city of Adullam; and as the seventh day was coming on, they purified themselves according to the custom, and kept the sabbath there. And on the day following, at which time it had become necessary, Judas and his company came to take up the bodies of them that had fallen, and in company with their kinsmen to bring them back unto the sepulchers of their fathers. But under the garments of each one of the dead they found consecrated tokens of the idols of Jamnia, which the law forbids the Jews to have aught to do with; and it became clear to all that it was for this cause that they had fallen. All therefore, blessing the works of the Lord, the righteous Judge, who maketh manifest the things that are hid, betook themselves unto supplication, beseeching that the sin committed might be wholly blotted out. And the noble Judas exhorted the multitude to keep themselves from sin, forsomuch as they had seen before their eyes what things had come to pass because of the sin of them that had fallen. And when he had made a collection man by man to the sum of two thousand drachmas of silver, he sent unto Jerusalem to offer a sacrifice for sin, doing therein right well and honourably, in that he took thought for a resurrection. For if he were not expecting that they that had fallen would rise again, it were superfluous and idle to pray for the dead. And if he did it looking unto an honourable memorial of gratitude laid up for them that die in godliness, holy and godly was the thought. Wherefore he made the propitiation for them that had died, that they might be released from their sin.

Now that we understand what Purgatory is and where it came from, we will address the second question.

Why do some denominations believe in it and others do not?

Some believe in Purgatory and others do not because they do not agree on the process of salvation.

The Catholics believe that one must participate in all the means of grace to be saved and purified.

The means of grace are:

The sacraments of Baptism and Communion

The sacraments of prayer and penance

The response to God's call.

Not everyone does these well. Thus, not every Catholic believer is a saint; only those who have been deemed worthy are saints. When they die, they enter directly into heaven with God.

Therefore, if you did not excel at practicing the means of grace in this life, you have to be purified to enter the presence of God.

The Protestants believe that salvation is God's work alone and that one must only believe in Jesus' death and resurrection to be saved.

There is nothing in this life or the next that can add to the work of Christ on the cross, which was validated with his resurrection. It is finished.

John Calvin wrote, “Purgatory is a pernicious invention of Satan, which renders the cross of Christ useless.” I would agree wholeheartedly.

Christ paid it all. He who knew no sin became sin, so that we might become the righteousness of God in Christ Jesus (2 Corinthians 5:21). Consider with me Ephesians 2:1-10

And you were dead in the trespasses and sins in which you once walked, following the course of this world, following the prince of the power of the air, the spirit that is now at work in the sons of disobedience— among whom we all once lived in the passions of our flesh, carrying out the desires of the body and the mind, and were by nature children of wrath, like the rest of mankind. But God, being rich in mercy, because of the great love with which he loved us, even when we were dead in our trespasses, made us alive together with Christ—by grace you have been saved— and raised us up with him and seated us with him in the heavenly places in Christ Jesus, so that in the coming ages he might show the immeasurable riches of his grace in kindness toward us in Christ Jesus. For by grace you have been saved through faith. And this is not your own doing; it is the gift of God, not a result of works, so that no one may boast. For we are his workmanship, created in Christ Jesus for good works, which God prepared beforehand, that we should walk in them.

This passage and many others make it clear that there is no need for the heresy of purgatory.

First, in verses 1-3, we were unfit for heaven, unfit for a relationship with God. It is who we were, but we all know it is not who we are.

Second, in verses 4-7, it is God who saved us now, not at the end of purgatory, but now. Now we are alive, now we are raised with him, now we are seated with him in the heavenly places. We are saints of God by his grace and his grace alone.

Lastly, in verses 8-10, we see the process of salvation by grace through faith. It is God’s work accomplished on the cross; the good works we participate in do not earn our salvation, they express our new identity in Christ.

Go, saints of God, created as his workmanship, doing the good works he has prepared in his presence, and know that to be absent from the body is to be present with the Lord (2 Corinthians 5:8).